What is the bladder?

The bladder is a balloon-like organ located in the lower abdomen.

It constantly inflates and shrinks to store urine. It connects to the rest of the urinary system via thin tubes: the ureters (which bring filtered urine from the kidneys) and the urethra (which carries the urine on its way out).

What is bladder cancer?

Bladder cancer is a disease where malignant (cancerous) cells develop in the bladder’s tissues and then start growing uncontrollably.

According to the American Cancer Society, the American healthcare system will see approximately 84,000 new cases of bladder cancer every year. These newly diagnosed patients will need reliable information to make informed treatment decisions.

A patient’s first visit to a cancer center is often marked by a barrage of difficult questions, covering everything from technicalities about the urinary system to experimental treatment options and their success rates. By learning the basics first, you and your loved ones can quickly build an effective partnership with the cancer care team and then focus on the significant decisions to come.

What are bladder cancer’s symptoms?

Typically, bladder cancer is diagnosed after noticing one of the following red flags:

- Blood in the urine (hematuria)

- Frequent urination

- A painful or burning feeling when urinating

- Chronic pain in the lower back

These symptoms are not exclusive to bladder cancer, and they may indicate anything from a urinary tract infection (UTI) to kidney stones or prostate cancer.

To narrow down the possibilities, doctors can try to find the mass via a CT scan or an MRI, or look inside the bladder by inserting a camera through the urethra (a procedure known as a cystoscopy). During this procedure, they will also try to perform a biopsy (removing a small piece of suspicious tissue, which a pathologist will then examine).

What are the different types of bladder cancer?

Bladder cancer specialists usually describe the disease using three different criteria:

- Where it starts (cancer type)

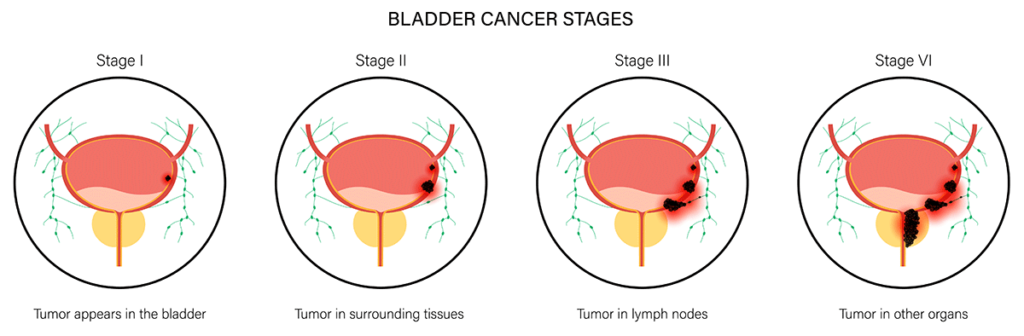

- How far has it spread (cancer stage)

Most cases of bladder cancer originate in the cells lining the bladder. Depending on the specific cell involved, the tumor may be classified as:

Transitional cell carcinoma

Also known as urothelial cells, transitional cells are flexible and can change their shape, allowing the bladder to expand and contract. Transitional cell carcinomas account for 90% of all new cases of bladder tumors, and they are considered the fourth most common cancer among American men.

Since it affects the inside of the bladder, this type of cancer will also cause symptoms earlier on. Approximately 70% of patients with transitional cell carcinoma will have their tumors caught early before they have invaded the surrounding muscle or organs.

Unfortunately, the outlook is not nearly as optimistic if left to its own devices. Once it becomes a “muscle-invasive bladder cancer,” the two-year survival rate drops to just 15% — meaning up to 85% of all people who develop a muscle-invasive case will die from the disease within two years.

Squamous cell carcinoma

Squamous cells are flat, rough cells that resemble fish scales. They are not normal in the bladder, but they can grow after repeated UTIs or from the chronic irritation of having a bladder catheter for a long time.

Adenocarcinoma

This type of cancer originates in secretory cells, which are small glands that produce mucus to help the bladder cope with long-term irritation. Like its squamous cell counterpart, it is associated with frequent infections or prolonged catheter use. However, adenocarcinoma is rare, accounting for 0.5-2% of all bladder tumors.

Any of these types of cancer also has several subtypes or specific mutations that can make it more or less aggressive. Noninvasive or ” low–grade” cancer cells are unlikely to grow back after removal, whereas a high-grade lesion may reappear a few years later and require more aggressive treatment.

What causes bladder cancer?

For most cases of transitional cell carcinoma, it is not possible to pinpoint a direct cause of the disease. However, some circumstances can increase a person’s risk of developing it. These risk factors include:

- Being male

- A family history of bladder cancer

- Occupational exposure to paints, arsenic, chlorine, and petroleum

- Smoking

- Using urinary catheters for a long time (over 1 year)

- Some bladder congenital disabilities

- Infections with Schistosoma haematobium, a type of parasite common in Africa and the Middle East

Bladder cancer treatment: How to get started?

When caught early, a contained bladder tumor can be removed entirely without damaging the surrounding organs. However, for more advanced cases, cancer specialists generally recommend a combination of oncology treatments and surgery.

After the initial cancer diagnosis, the treatment plan will depend mainly on how advanced the disease is. It can involve cancer surgery alone or combined with chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or immunotherapy.

For patients with a superficial disease and a low-grade lesion, a simple surgery known as transurethral resection or TUR may be enough. This involves entering the bladder with a cystoscope and either scraping or burning the tumor away.

If the cancer has invaded the wall of the bladder and not just the inner lining, doctors may resort to more complex surgeries.

Partial cystectomies

This surgery involves removing part of the bladder. It is typically used when a TUR is insufficient, but the tumor is confined to one side of the bladder.

After removing the affected part, surgeons will then stitch the bladder back together. The result will generally be a smaller but still functional bladder. After a partial cystectomy, patients can still urinate normally, although they may need to do it more often.

Complete and radical cystectomies

Complete and radical cystectomies involve removing the entire bladder (complete procedure) or the full bladder, surrounding lymph nodes, and occasionally, the prostate, ovaries, and uterus.

Creating an alternative path for urine to flow without a bladder is necessary. This is a type of reconstructive surgery known as a urinary diversion. There are many ways to do this:

- An old-school ileal conduit, where a new bladder is created from the small intestine and connected to an external bag

- A continent cutaneous or “Indian pouch” creates a more flexible bladder that can be emptied using a thin tube 4 times daily.

- An orthotopic bladder or neobladder is created using small intestine tissue and connects it to the urethra, allowing the patient to urinate normally.

Nowadays, cutting-edge techniques such as robotic surgery and bioprosthetics can produce more precise results. However, the more the cancer has spread, the more complex and riskier it will be to perform a high-tech neobladder procedure.

Localized oncology treatments

After a TUR or partial cystectomy, medical oncologists can deliver anti-cancer treatments directly inside the bladder. In this way, they can “kill” any cancer cells that may have been left behind after surgery.

They are usually delivered using a thin tube and essentially “flush” the inside of the bladder with either chemotherapy or immunotherapy drugs. As they remain inside the bladder, they generally have milder side effects than traditional treatments.

Systemic anti-cancer treatments

Systemic, or “whole body” treatments include:

- Traditional chemotherapy, given via IV, to stop the growth of cancer cells

- Radiation oncology therapy uses external beam rays to kill cancer cells

- Targeted immunotherapy drugs help a patient’s immune system identify and target specific cancerous cells.

Advanced or recurrent bladder cancer is considered a potentially lethal disease. It typically requires consultation with various specialists, including hematology, medical oncology, and radiation oncology. In addition, patients recovering from a complete or radical cystectomy can also benefit from enlisting other support services, such as counselors or occupational therapists.

Why trust Tower Urology for your bladder cancer care?

Tower Urology’s board-certified urological team has been a leader in effectively treating cancer for over two decades, with specialists trained in all aspects of prostate health.

Tower Urology is a proud affiliate of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, ranked #1 in California and #2 nationwide by U.S. News & World Report. This partnership reflects our dedication to delivering the highest standard of urologic care alongside the best urologists in Los Angeles.

Our years of experience and access to Cedars-Sinai’s world-class facilities ensure that our exceptional and innovative urological care positions Tower Urology as a leader in Southern California.

We invite you to establish care with Tower Urology.

Tower Urology is conveniently located for patients throughout Southern California and the Los Angeles area, including Beverly Hills, Santa Monica, West Los Angeles, West Hollywood, Culver City, Hollywood, Venice, Marina del Rey, and Downtown Los Angeles.

Our services include treatment for bladder and urologic cancer, kidney cancer, prostate cancer, testicular cancer, and cancer fertility management.

Bladder Cancer Frequently Asked Questions

Nowadays, it is easy to assume that the best doctors are the most specialized ones. However, this is not necessarily the best choice for a new patient. Many specialists are naturally biased toward the type of treatment they perform the most: surgeons want to operate immediately, radiation oncologists will immediately propose radiation, and so on.

In such cases, we should not overlook the value of a slightly less “zoomed-in” approach. An experienced urologist should be the first port of call, and even after involving another specialist, they can continue to provide more holistic patient care — while still deferring to the experts when necessary.

The hematology/oncology fields are among the most rapidly changing. Many experts are continuously testing new protocols and treatment combinations for all types of cancer. Advanced cases or rare mutations can offer opportunities that a regular cancer center can’t.

Many clinical trials have specific criteria for their volunteers, from age and gender to particular mutations. Current trials can be viewed at ClinicalTrials.gov or the National Cancer Institute’s database.

Patients facing a complete or radical cystectomy are often understandably anxious about life after surgery.

The initial recovery usually takes 6 to 8 weeks. Following this, it will depend on the exact type of diversion done. If you have an ileal conduit, you will need to learn how to deal with an external pouch — which may require you to alter your clothes slightly, change the bag, and care for the opening or stoma at home.

An Indian pouch offers more privacy, but learning to empty it quickly may take some practice.

Finally, patients who opt for a neobladder will also need to relearn bladder control to prevent incontinence and retention. Sometimes, the surgery can affect nearby nerves, which may result in sexual dysfunction.

Despite these changes, most patients adapt well to their new routine with proper support and education. Regular follow-up care will help monitor your recovery and address any concerns.